No Longer Hip

Author: Sean Aubuchon, MD

Peer-Reviewer: Justine Ko, MD, CAQ-SM

Final Editor: Alex Tomesch, MD, CAQ-SM

A 77-year-old female with past medical history significant for Parkinson’s disease and hypertension presents to the ED after a mechanical fall upon getting into bed. Since that time, she has endorsed left hip pain and inability to ambulate.

Image 1 and 2. Plain radiographs of the patient’s left hip. Author’s own images.

What is the diagnosis?

This is an intertrochanteric femur fracture.

-

Pearl: Intertrochanteric femur fractures are a common injury seen in the emergency department. In fact, about half of all femur fractures annually are intertrochanteric femur fractures. They are described as extracapsular fractures of the proximal femur at the level of the greater and lesser trochanter [1,2].

What are expected physical exam findings?

Classically, proximal femur fractures present with a shortened leg that is externally rotated and abducted in the supine position. Ecchymosis and swelling may be present. Patient’s will have painfully limited hip range of motion. There can be tenderness to palpation within the inguinal area and the proximal thigh.

Which imaging modalities can be used? Is there a role for other diagnostic modalities such as ultrasound?

Radiographs are the gold standard imaging modality. Recommended views include an AP pelvis, AP hip, cross table lateral, and a full length femur film [2]. CT and MRI are typically not indicated, but due to their high specificity can be used when there is high clinical suspicion and initial films are negative.

Ultrasound (Image 3 & 4), however, may offer an accurate means for diagnosis. Though sensitivities and specificities of ultrasound in diagnosis of femur fractures have not been well described, some authors have attempted to explore its utility. Bozorgia et al. found that ultrasound has a 90% sensitivity for detecting femur shaft fractures in adults [4]. The benefit of ultrasound is that it can rapidly be incorporated into a physician’s initial evaluation of a patient, potentially reduce the necessity of painful manipulation required by radiographs, and allow for simultaneous evaluation for ultrasound-guided regional nerve blocks.

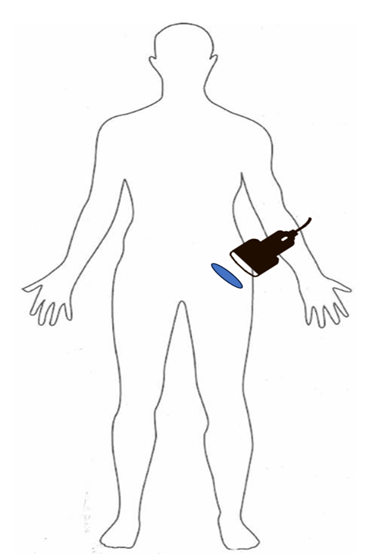

Figure 1. Suggested initial orientation of the ultrasound probe to evaluate the femoral neck and proximal femur. Author’s own image

Image 3 and 4. Linear (top) and curvilinear (bottom) ultrasound show a cortical irregularity (blue arrow) at the level of the femoral neck/intertrochanteric femur. Author’s own images.

What is the management in the ED?

Patients can have significant blood loss from fractures in this region, so monitor for signs of hemorrhage. Prompt resuscitation may be necessary. Monitor for signs of compartment syndrome.

Traction splints are often not necessary. You can consider placing a pillow or blanket under the knee to keep the hip in slight flexion. Traction splinting is only considered if there is significant neuro-vascular compromise, however these patients should ideally be taken immediately to the operating room [5].

Acute pain management is important. Consider a multimodal approach.

When do you consult Orthopedics?

Patients with neurovascular compromise require an immediate emergent reduction.

Orthopedics should be consulted in the ED for intertrochanteric hip fractures. Unless a patient is non-ambulatory or has an exceedingly high perioperative mortality, then operative treatment is almost always indicated. The type of surgical treatment is based on the fracture pattern. There are four main options: sliding hip screw (SHS), cephalomedullary nail (CMN), open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF), and arthroplasty. The most common technique is CMN as it can be used in unstable fracture patterns and can be performed using a closed technique [7,8].

References

[1] Emmerson BR, Varacallo M, Inman D. Hip Fracture Overview. InStatPearls [Internet] 2023 Aug 08. StatPearls Publishing.Available;https://www.statpearls.com/articlelibrary/viewarticle/22890/

[2] Attum, B., & Pilson, H. Intertrochanteric Femur Fracture. In StatPearls [Internet] 2023 Aug 08. StatPearls

[3] Zuckerman J. D. (1996). Hip fracture. The New England journal of medicine, 334(23), 1519–1525. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199606063342307

[4 ]Bozorgia, F., Azarb, M. S., Heidaria, S. F., & Khalilianc, A. (2017). Accuracy of Ultrasound for Diagnosis of Femur Bone Fractures in Traumatic Patients. Journal of Clinical & Experimental Orthopaedics, 3(1:27). https://doi.org/10.4172/2471-8416.100027

[5] Handoll, H. H., Queally, J. M., & Parker, M. J. (2011). Pre-operative traction for hip fractures in adults. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews, (12), CD000168. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD000168.pub3

[6] Girón-Arango, L., Peng, P. W. H., Chin, K. J., Brull, R., & Perlas, A. (2018). Pericapsular Nerve Group (PENG) Block for Hip Fracture. Regional anesthesia and pain medicine, 43(8), 859–863. https://doi.org/10.1097/AAP.0000000000000847

[7] Chlebeck, J. D., Birch, C. E., Blankstein, M., Kristiansen, T., Bartlett, C. S., & Schottel, P. C. (2019). Nonoperative Geriatric Hip Fracture Treatment Is Associated With Increased Mortality: A Matched Cohort Study. Journal of orthopaedic trauma, 33(7), 346–350. https://doi.org/10.1097/BOT.0000000000001460

[8] Fischer, H., Maleitzke, T., Eder, C., Ahmad, S., Stöckle, U., & Braun, K. F. (2021). Management of proximal femur fractures in the elderly: current concepts and treatment options. European journal of medical research, 26(1), 86. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40001-021-00556-0